Toy Machine

Toy Machine

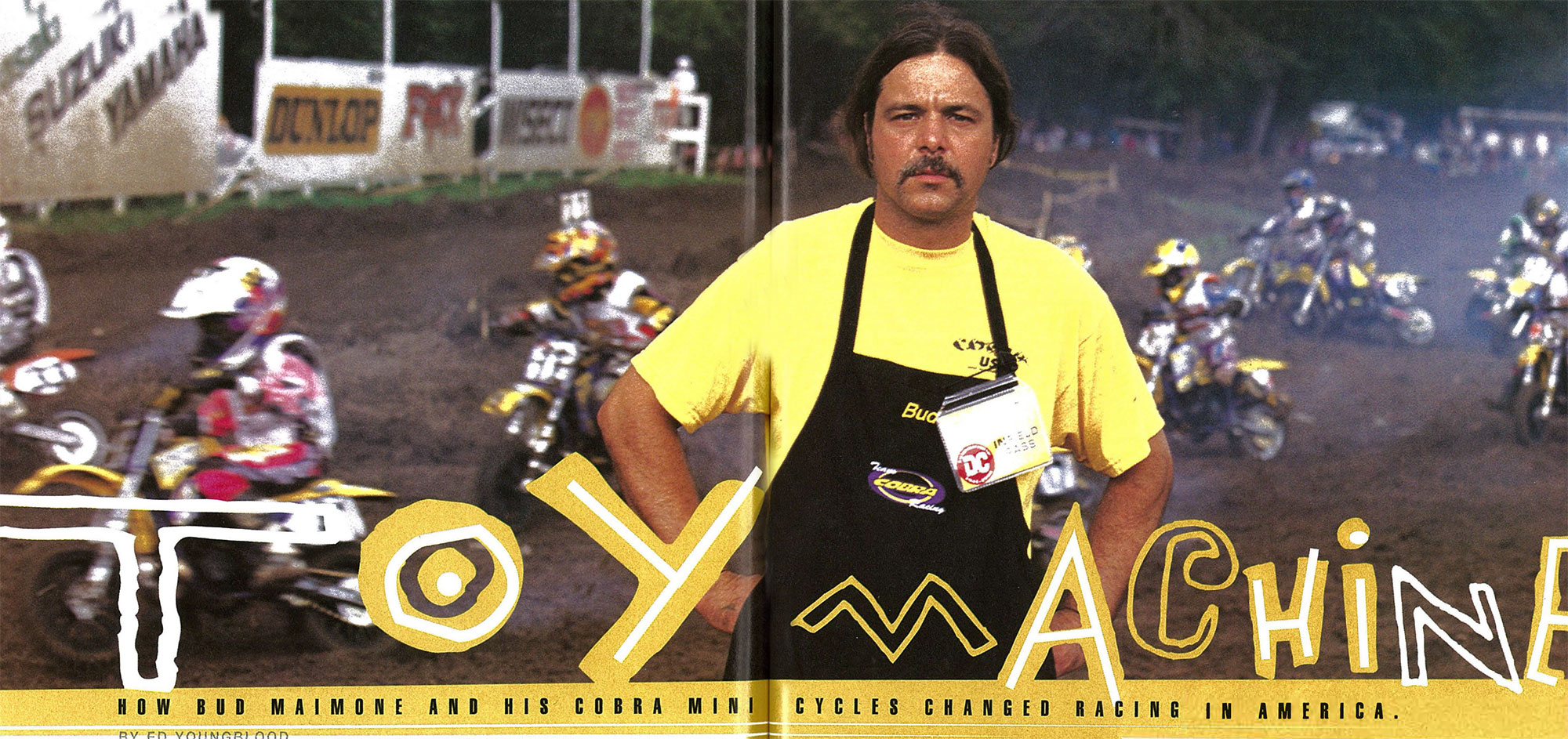

How Bud Maimone and His Cobra Mini Cycles Changed Racing in America

By: Ed Youngblood

BUD MAIMONE COMES ACROSS a lot younger than his 43 years. He is physically trim and has a youthful face and a long ponytail. But you begin to understand the remarkable depth of his technical knowledge and experience when he starts enthusiastically talking about what goes on in his small machine shop just south of Youngstown, Ohio. The shop is where Maimone’s controversial Cobra minicycles are designed and manufactured. It is the place where a big idea took shape, one that has revolutionized beginner-level motorcycle racing throughout America.

Minicycle racing in America is big business. Minibikes are the likely point of entry into this sport for young riders and their parents, and manufacturers hope to attract these new customers in the hopes of keeping them throughout their motorcycling days. A Honda rider might go from a Z50 to a CRS0, then up to the 125s and 250s. Away from motocross, the hope is that the family will continue to buy Honda products, like a street bike or an automobile. By adding up the potential purchases over the years, it becomes clear why the minicycle market is so important.

However, until recently, the manufacturers’ battle lines disappeared when one looked below the 80cc level. For years the junior minicycle field -for the youngest of riders, ages eight and under -remained stagnant as far as growth and competition goes. Yamaha had a lock on the market with their wildly popular “YZinger” automatic. A simple, shaft-driven minicycle for beginning riders, it wasn’t surprising to see full starting gates of the little Yamahas at motocross races all over the country-hardly anyone else was making race bikes that small. Actually, the YZinger wasn’t really a race bike itself; it was more like a toy which changed very little from year to year.

That’s what brought Maimone into the junior minicycle business -he wanted to build a machine. He wanted to do it in his own shop. On his own terms. With his own people. And his goal was not to build a customer relationship that would last throughout a rider’s motorcycling years -there’s no such thing as a Cobra 60 or beyond. Instead, Maimone seized what all good entrepreneurs look for: An opening in the market.

BUD MAIMONE DID NOT START OUT as a motorcycle manufacturer. His father died when he was three, and he was raised in a poor family shuttling back and forth between Pittsburgh and Youngstown as his mother’s job was transferred from time to time.

“I could not afford to race,” he says, “but I always loved motorcycles. I got a minibike when I was eleven and customized it. I didn’t have a machine shop or anything to work with. I just kind of did it with hand tools and a hacksaw in our apartment, and I won a trophy at the Canfield, Ohio fair.” Pursuing his creative manual skills, Bud became a tool and die maker, and in 1983 he and his wife Sunny opened Mainstreet Molds, their own machine shop and pattern making business located in New Middletown, Ohio.

Eventually they bought their son Brett what Bud calls a “yard bike,” and after getting his fill of riding in the yard, Brett wanted to go racing. Minicycle racing at that time was basically Yamaha PW50s-the Y-Zingers-and a few European brands powered by Moto Morini engines.

“They were nothing but yard bikes, and most of them still are,” Bud says. “They’ve made them look like motocrossers and put fancy graphics on them, but they’re not engineered and built for the punishment that goes with racing.”

“I came up with the idea after Loretta Lynn’s in August of ’93 to build a better minicycle,” begins Maimone. “The bikes that my son Brett was riding were breaking all the time -he could have won his class at Loretta Lynn’s, but his bike broke. I called the importer to find out if there were any changes coming along for ’94. I wasn’t satisfied with the few changes that he said would be made and told him that if they didn’t do more, I would produce my own bike. I wanted a different shock, different fork-just a better overall bike. They didn’t take me seriously-they kind of laughed at me.”

They laughed because they didn’t know that Maimone, a tool and dye maker by trade, has a million dollars worth of equipment in his Mainstreet Molds machine shop, with which he can virtually build anything. For instance, he makes the gun sites used for 41mm grenade launchers purchased by the U.S. Government. For the automotive industry, he makes the molds that hold windshields for shipping. He also makes pedals for Huffy bicycles and toner cartridges for Canon and Ricoh copiers. As a matter of fact, the serving platter for turkeys that your family sits around every Thanksgiving more than likely came from a mold that Bud Maimone built for Rubbermaid.

Maimone’s first step was to com·e up with a name, and for that he tapped his love of a famous car. “I’ve always admired the Shelby Cobra. As a limited production, high quality, high performance vehicle, it projected exactly the kind of image I wanted my product to project.”

MAIMONE WAS SURE HE KNEW HOW to build a better motorcycle, but he now admits that he had no idea what he was getting himself into.

“I called the AMA and told them what I wanted to do,” he says. “They didn’t believe I was serious. Or maybe

they knew I was serious, but had no idea what was required.” Of course, what Bud learned was that in order to race in AMA sanctioned events and in the amateur national championship program he couldn’t just build a better motorcycle for Brett; he had to become a manufacturer. He learned that the rules required him to build at least 200 identical, serial production models and to have them counted and approved by the AMA.

Undaunted, he set out to have his new Cobra ready for the 1994 racing season. Fortunately for Bud, the AMA Congress reduced the number of vehicles required from 200 to 50 for 1994.

“I second-mortgaged my business, second-mortgaged my house, and laid everything on the line to start building bikes,” says Maimone. “By January 15 of ‘941 was in production, making my own frames. I flew over to Italy to hook up with Marini Franco on the first engines, and got one together.”

Maimone debuted the bike at a CRA Banquet in Ohio to much praise. However, the industry did not exactly welcome the bike with open arms. Companies that were supplying parts to both the new Cobra venture and existing junior minicycle brands were caught in the middle of a new battlefield, and it was the upstart Cobra that suffered as a result

“They cut off my radiators, my wheels, and my plastic due to this sudden conflict of interest,” recalls Maimone. “Marini of Italy came to my rescue because they wanted to sell me motors and hooked me up with new people”

New parts suppliers meant that Maimone had to go back to the drawing board, scrapping hundreds of “It was 20 hours a day, seven days a week, in designing this bike just to get it ready for the ’94 season,” remembers Maimone. “The first production should have been done in late January, but we didn’t get the bikes together until June.”

And that’s where the rub was with the AMA. The sanctioning body’s magic number for homologation was 50 units, which had to be built and available to the public by that time of the year. While the revolutionary Cobra was causing a tremendous buzz around the minicycle pits, parents were finding it hard to get their hands on one of the yellow flyers. Adding fuel to the growing fire was the fact that Brett did have one of the bikes. And when he won on the bike at the AMA Amateur National Championships at Loretta Lynn’s, a roar of disapproval went up in both the minicycle and media circles. While the parents of other riders claimed that Maimone had held back bikes in order to give his son an advantage, some magazines took him to task for the frequent breakdowns of the rare ones that were available. It only hardened Maimone’s resolve to make more and better bikes.

Maimone’s fledgling Cobra company had proven itself by winning a national championship at Loretta Lynn’s, but he was faced with the realization that being a manufacturer brings a lot of headaches, especially when your product needs to survive in the competitive and emotionally-charged environment of minicycle racing.

“People really started badmouthing us and spreading damaging rumors when the Cobras started winning,” said Sunny Maimone. “They said we were cheating. They said there were no two Cobras alike. They said we were giving special products to rich customers. They said we had the AMA in our pocket. And they told people we were going out of business and that our customers would be high and dry with no parts and no support.” Both Bud and Sunny readily admit that, had they known the production problems they were going to run into, and the mean-spirited tactics at the retail level, they never would have created the Cobra.

Just for the record, the AMA’s Hugh Fleming denies that Cobra ever skirted the approval rules or got preferential treatment.

“Bud never cut any corners,” he says. “When we realized the potential of his product, we knew the traditional minicycle companies were really going to put him in their sights. We were very careful about enforcing the approval rules with Cobra, because we knew a lot of people would be trying to find fault with the AMA if they couldn’t find fault with his motorcycle.”

“AT THE END OF THE 1994 SEASON we sat down and really talked it out,” remembers Maimone. “We wondered whether we wanted to be doing this. But by then we had about $300,000 invested in the development of the motorcycle, and I decided we had something to prove.”

Maimone put his head down and his skeleton crew to work. His son Brett joined him on the assembly line, having decided to hang up his helmet – perhaps a result of the stinging controversy that came with his championship. Committed to remaining in the market, Bud began to systematically redesign, build, and replace, one-by-one, the problematic components that brought the early Cobras so much criticism.

“Having the best product out there is key to the Cobra image and reputation, but I also wanted to have total control,” admits the builder. “If a part went wrong, we wanted to know why and fix it quick, and the only way to really do that is if you build it yourself. We even know what shift each engine is built on, and who built It.”

Cobra has bitten deep into the market share since its 1994 maiden season. By the ’95 version of Loretta Lynn’s, more than half of the 51cc class would be sitting aboard Cobra machines. The proof of class dominance was unmistakable in ’98, when 78 of the 84 machines entered in Loretta Lynn’s two 51cc classes were Cobras.

The company ·plans to sell over 300 motorcycles in 1999. KTM sells significantly more of its 50cc product, but the great majority of these become play bikes and never tum a wheel in sanctioned competition. In the 50cc market niche for competition minicycles, Cobra has grown from nothing to market dominance in five years.

THE AREA SURROUNDING THE COBRA FACTORY in New Middletown, Ohio, doesn’t seem a likely place to find someone building competition minicycles. Rather, it seems more appropriate for the building and distribution of Amish furniture, which is offered for sale from various merchants along the Ohio roads. Little fanfare comes with the machine shop. It looks no different than most others, only inside a man is using a modified Big Busterbrand long-splitter to press triple clamps. With less than 6,000 square feet of space for storage, manufacturing, and assembly, it seems almost inconceivable that the company has come this far. But cramped and cluttered quarters do not appear to be in Cobra’s future; the footers are already in place for a new 52,000 square foot facility adjoining the company test track.

There are now 14 people who work at Cobra in manufacturing, assembly and shipping. (When the first bikes were being put together, the work force included Bud’s wife Sunny and two of his in-laws.) The company payroll has expanded, but Sunny remains the president of Cobra, Inc., and Bud is the visionary and maker. And because Maimone machines much of his own parts, his own liquid-cooled engines (suspension components, sprockets, cast aluminum wheels and more), there are more parts being built internally by Cobra than just about any other manufacturer produces in-house. As a matter of fact, over 90 percent of the pieces of the 1999 King Cobra were manufactured in America. The only parts still coming from overseas suppliers are some of the body work, cables, electrics, and radiators. Bud says with a certain amount of pride, “One guy came to visit our operation and he said, ‘You know, you’re building the very first American-made off-road motorcycle.’ I hadn’t thought about it until then, but I believe he was right.”

As he learned more about selling and servicing a product, Bud also realized that product reputation was going to depend, to a certain extent, upon the sophistication of his customers.

“Since the 50cc class is the first place where young families go racing, a lot of the newcomers just don’t have a clue,” he explains. “They think going racing is just kind of an extension of playing in the yard, and some of them have no idea about maintenance or bike setup. We learned there are fathers out there who don’t even realize they should change the crankcase oil.” Of course, no maintenance or improper maintenance under racing conditions results in failures, and the bike gets the blame. To reduce this problem Cobra put a support trailer on the road and Bud began to conduct Cobra Clinics at major events. In addition, each year the company conducts a training camp and cookout for its customers over the Fourth of July weekend.

“We’re not trying to teach kids how to ride,” Bud explains. “But we get them out on our own test track to show them and their parents how to set up the motorcycle, how to make adjustments, and how to do proper maintenance and preparation.” He adds, “And we don’t limit it to Cobra owners. We welcome minicycle riders on any brand because we figure it is good public relations, and that is good for our business.”

As Cobra leads the way in putting a hotter product in the hands of youthful competitors, it is only natural that some people will raise safety issues. Is it really advisable to give minicycle riders a more potent product? Sunny Maimone puts forward an interesting theory.

“I think the problems came when kids had to move from the little play bikes to the 60s and 80s,” she says, “which were real racers with gearboxes and more powerful engines. It’s a pretty big step for little kids, and I think having access to a bike like the Cobra better prepares them for it.”

Whether or not this theory is correct, the AMA’s Fleming confirms that the advent of a better minicycle has not created a safety problem.

“Early on, some people got really alarmed about the Cobra concept,” he says, “saying a motorcycle like this was too much for little kids and that more people were going to get hurt. We just haven’t seen that. Injuries have not increased in the class since the Cobras came on the scene.”

HAVING OVERCOME ITS ROCKY START IN 1994, the future looks pretty bright for the Cobra company. Product development continues and a bigger manufacturing facility is on the way. Bud’s eyes light up if you ask about future Cobras, but at the moment h’e’s not saying much.

“I plan to revolutionize the 50cc class once again,”he says about his upcoming 2000 model. “We’re going to render everything obsolete! What we’re doing meets all of the specs, but I expect a big hassle from both the AMA and the NMA because it will change everything.” The AMA, however, seems to be getting used to Cobra’s creative solutions.

Fleming says, “Bud brought an idea into the sport and followed through. He’s always done everything by the book. Other people say he pushes the rules right to the edge, but what really successful tuner or designer doesn’t? That’s what racing development is about.” When confronted with the rumor that KTM is coming out with a Cobra killer, Bud says, “I’m not concerned.

I welcome the competition. We’ll just keep building the best bike we can and continue to concentrate on quality and dependability. Trick doesn’t count if you can’t finish the race. We believe that if we keep making a bike that keeps running, our owners will be able to make them keep winning.” But Bud won’t take all the credit for that quality. He adds, “All of our employees are from families who have raced or been involved in motocross. They really care about what they’re doing, and they put that care into the fabrication and assembly of the product. They act like they own the company.”

Five years later, there is no doubt that Cobra has breathed new life and excitement into 50cc racing. As proof of that, nine brands and fourteen models have been submitted to the AMA for approval for competition during the 1999 season, all of which bodes well for the future of motocross in America.

“When I built this bike, the whole idea was to upgrade the class,” says Maimone. “The Cobra was the first fullblown motocross racing minicycle for riders at that level. It’s not a toy- it’s a machine. And we tell people that when they call. We don’t want them to think it’s just a yard bike; it’s rriade specifically for racing. I knew that if we built a good, dependable, race-ready bike, we would sell as many as we could make.”

Bud Maimone was right – the product is a better minicycle, and it sells out each year. And that’s what makes his story an American success.

0 comments